Teaching Without Borders: Can Digital Learning Solve the Recruitment Crisis?

Naomi HowellsEducation Today Articles

Naomi HowellsEducation Today Articles

There has always been a connection between geography and schooling. The accessibility and selection of a school's faculty have historically been influenced by its physical location. Finding new staff has been particularly challenging in certain regions, such as those that help underprivileged learners, coastal towns, and rural places. Contrarily, many qualified educators are unable to relocate due to financial constraints, caregiving obligations, health concerns, or rigid job schedules.

What if geography no longer had an impact on who could teach where or even how individuals could learn? This is a huge question that is emerging as digital learning continues to evolve.

Particularly impacted are alternative and referral services due to a lack of teachers in such regions. Because of the high level of physical presence often required for these positions, the application pool is relatively tiny. Teachers may need to relocate or even live on-site in certain situations to ensure that children in need receive the care they require. Although this degree of commitment is admirable, it limits the number of people who can actually take the lead.

Cillian Murphy's portrayal of a teacher assisting economically disadvantaged students in a recent film highlights this issue in the media. As the anecdote so eloquently demonstrates, being physically there at all times is sometimes mistaken for commitment, and roles that demand complete absorption can be emotionally and personally taxing. Acknowledging the effort that goes into it, these depictions also highlight systemic obstacles that prevent some individuals from participating.

One approach to removing these obstacles without compromising on quality is digital learning. In an effort to make education more accessible, a local organisation that runs referral units for low-income youngsters is utilising digital learning powered by artificial intelligence, according to a director we spoke with this week. They assist kids who are unable to attend a traditional school setting due to factors including social exclusion, anxiety, or medical concerns. It is common practice to instruct these pupils remotely. Digital provision is not a secondary choice for these pupils; it determines whether they may participate or not.

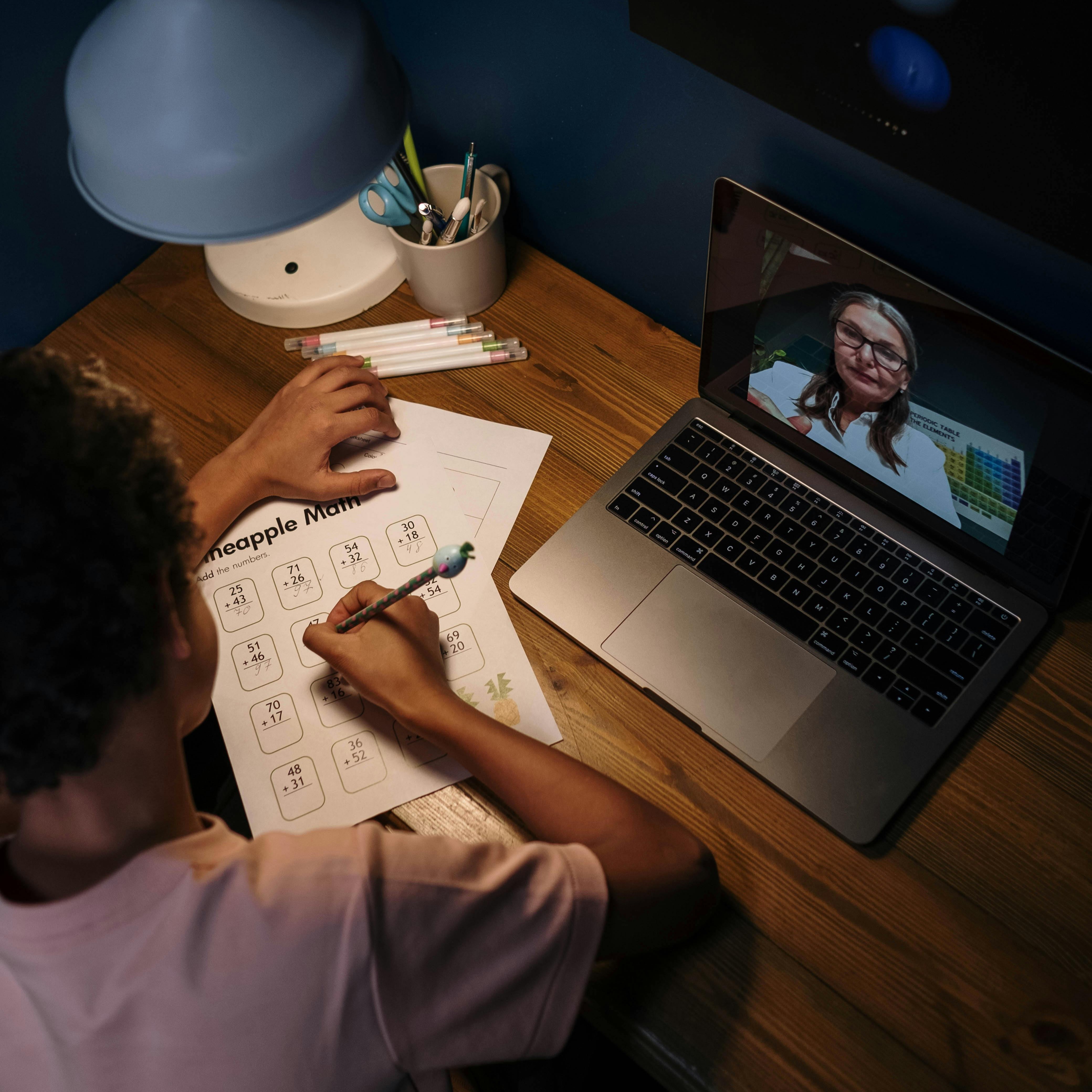

Thanks to AI-powered platforms, qualified educators may collaborate with students remotely, eliminating the need for physical locations or relocation. Specialist help may be more easily scaled, and provision stabilised in areas where hiring has long been challenging when knowledge is shared across regions.

A broader spectrum of candidates can be considered for open positions as a result of this shift, including semi-retired professionals seeking meaningful, flexible work, teachers unable to relocate, individuals with caregiving responsibilities, and experienced educators who have left the profession due to burnout. Rather than losing this knowledge, digital models help education keep and apply it better.

Claiming that online education can supplant face-to-face instruction is incorrect. Particularly in alternative education, special education, and neurodevelopmental assistance, intervention work, and in situations where staffing levels are inadequate, its value lies in its unique and combined application. When paired with on-site pastoral care and well-defined safeguarding mechanisms, digital delivery can be more consistent than conventional recruitment strategies.

Employers should have the same flexibility as students when it comes to learning locations. Borderless education is no longer an abstract concept. We can now take this opportunity to build a more inclusive, flexible, and sustainable education workforce by judiciously incorporating it.